Henry A. Kissinger was the 56th Secretary of State, a respected American scholar and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate who helped create the post-World War II world order and led the U.S. through some of its most complicated foreign policy challenges.

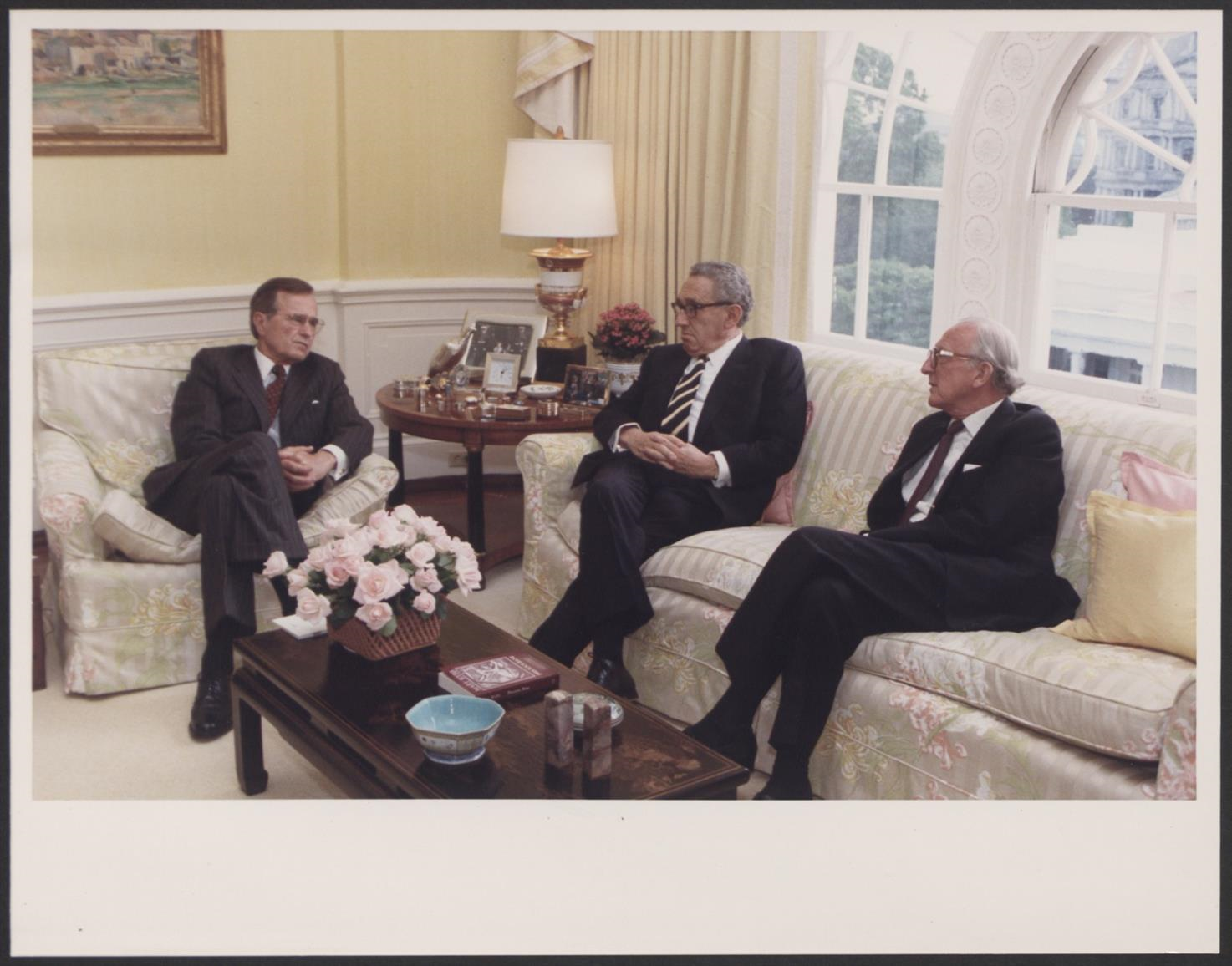

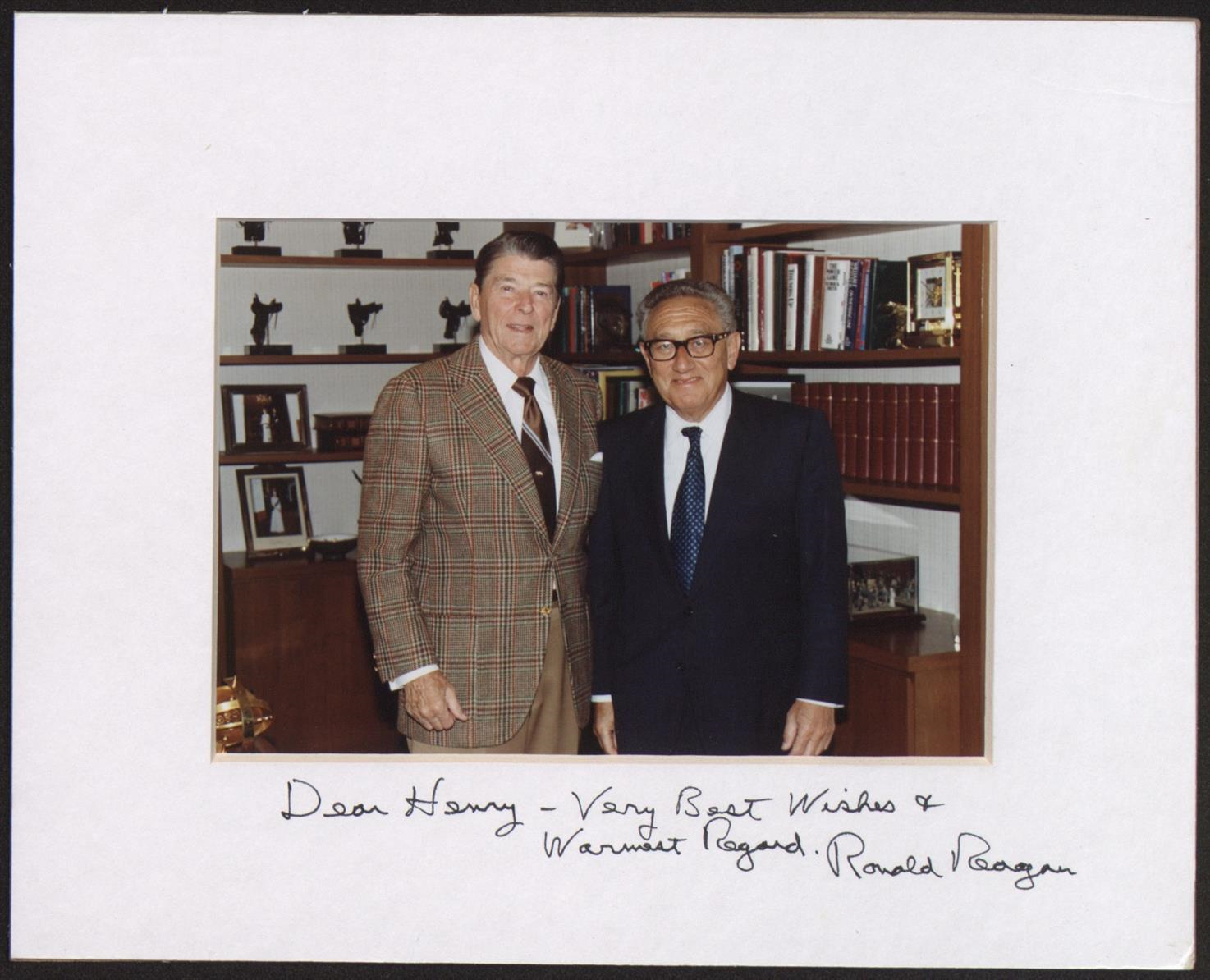

With his distinct German accent, sharp wit, voluminous writings and belief in the peacemaking power of realpolitik, Dr. Kissinger was one of the most influential foreign policy and national security practitioners of the post-World War II era and remained active in national security for more than 70 years. From the age of 20, when he joined the U.S. Army, to nearly his death, Dr. Kissinger continued to travel to Washington to offer testimony on U.S. national security strategy.

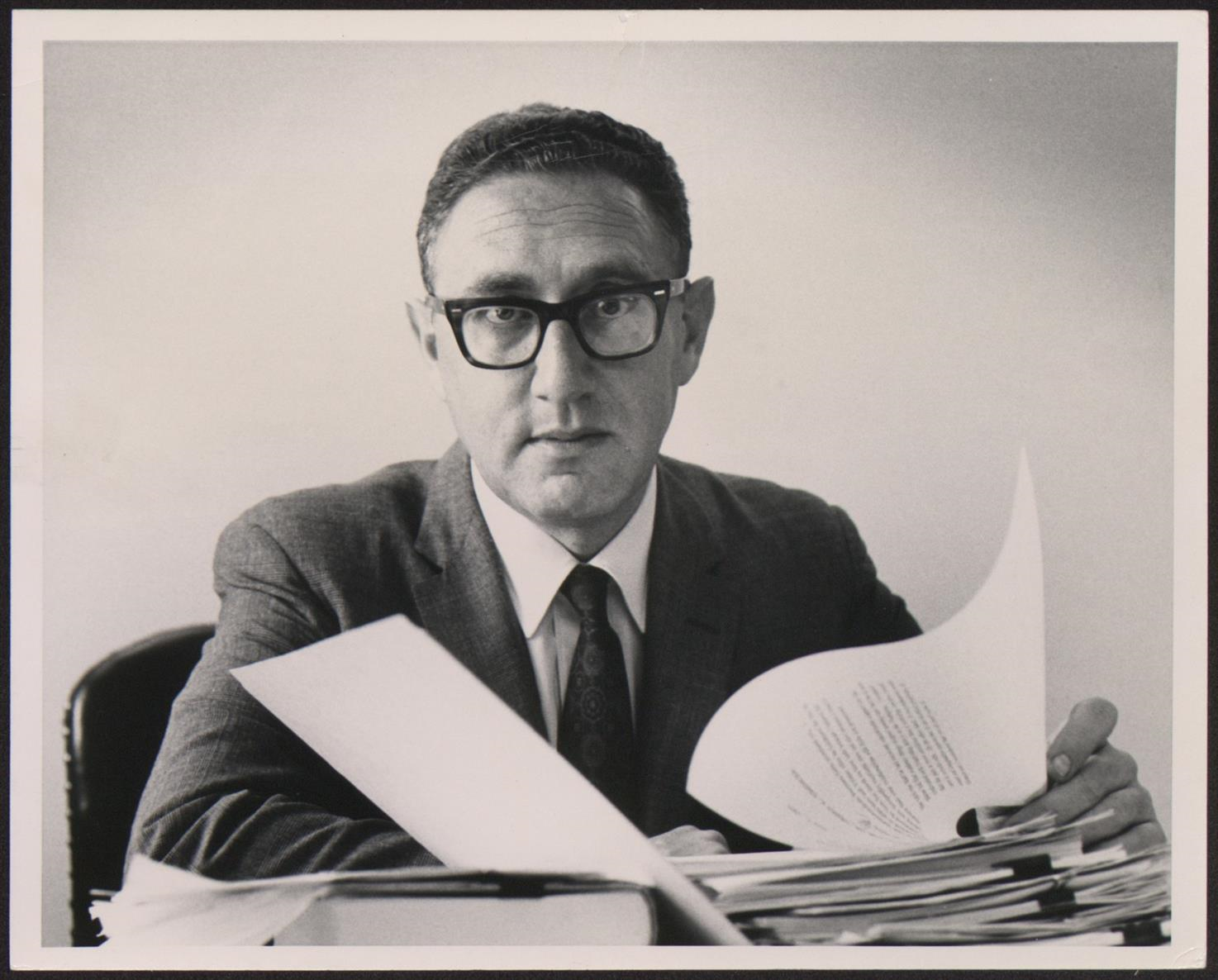

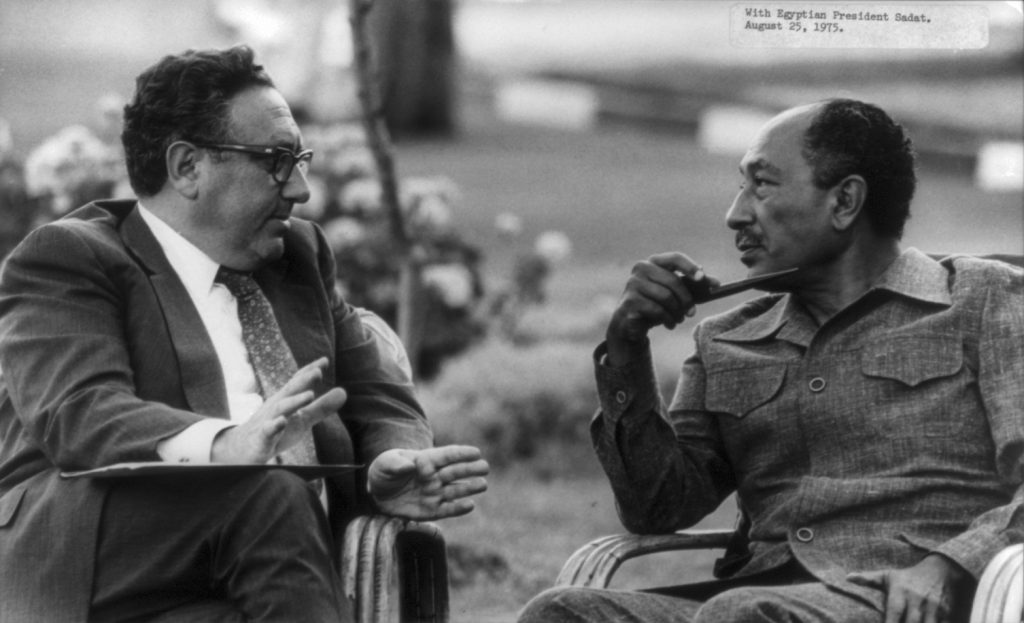

As National Security Advisor and then Secretary of State during the Nixon and Ford Administrations, Dr. Kissinger was the author of some of those administrations’ most important, and sometimes controversial, policies.

He was instrumental to opening China to the Western world and was the primary voice of détente with the Soviet Union that lowered tensions during the Cold War, a reflection of his belief in the balance of power as a tenet of global order.

Before his government service, Dr. Kissinger served on the faculty at Harvard University, where he ran the International Seminar from 1952 to 1969.

Dr. Kissinger is the recipient of a number of awards and recognitions. In 1945, he was awarded a Bronze Star from the U.S. Army for meritorious service. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973, the same year a Gallup Poll of Americans listed him as the most admired person in the world. He was also awarded the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in 1977 and the Medal of Liberty, given one time to ten foreign-born American leaders, in 1986.

As the architect of a lasting era of peace, stability, prosperity and global order, he made a substantial impact on generations of citizens, from the U.S. to Europe and China.